Science Olympiads

The Science Olympiads or Knowledge Olympiads are a set of educational environments focused on high school students, developed in Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th century – maybe with the Romanian Licei Competitions in 1885, maybe with the Hungarian Mathematics Competition in 1892, both accompanied by magazines for problem-solving and popularization of science (Recreaţii Ştiinţifice in Romania, Középiskolai Matematikai és Fizikai Lapok in Hungary). This happened simultaneously to the idea of a modern (sports) Olympic competition, led by the French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin and whose first edition also happened in 1892. Coubertin was answering to the popularity of sports associations in European societies, but also taking inspiration from the Ancient Greek festivals in Olympia and other places, that were bigger things, true religious celebrations of human excellency in several dimensions.

On the other hand, these high school science competitions were also simultaneous to other important educational movements, especially the writings of John Dewey in the U.S., later developing into project- and problem-based learning methods. However, the high-school competitions only got the name "olympiad" in the Soviet Union, first with the so-called Leningrad and Moscow Mathematics Olympiad (Ленинградская / Московская математическая олимпиада) in 1934 and 1935. The problem-based competition, hand in hand with the famous Mathematical Circles, was very successful in approaching edge-on academic research to curious and talented school students, so the model quickly spread through all the Sovietic industrial centers, and also got replicated in other science subjects: physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology etc.

The format slowly spread through other countries, eventually leading to cross-country collaborations and finally to the International Olympiads of Mathematics (IMO, in 1959, Physics (IPhO, in 1967), Chemistry (IChO, in 1968) — and also Linguistics, among the younger siblings, in 2003. In each region of the planet, the science olympiads went on to take shapes suited to each context: be it developing high-level young scientists, supporting the technological sector, raising science education and awareness on a broader societal scale, etc. Nowadays, every year we have hundreds of millions of students participating every year in one or more science olympiads, which creates a big and widespread impact. In Brazil alone, the Brazilian Mathematical Olympiad for Public Schools has around 19 million students participating per year.

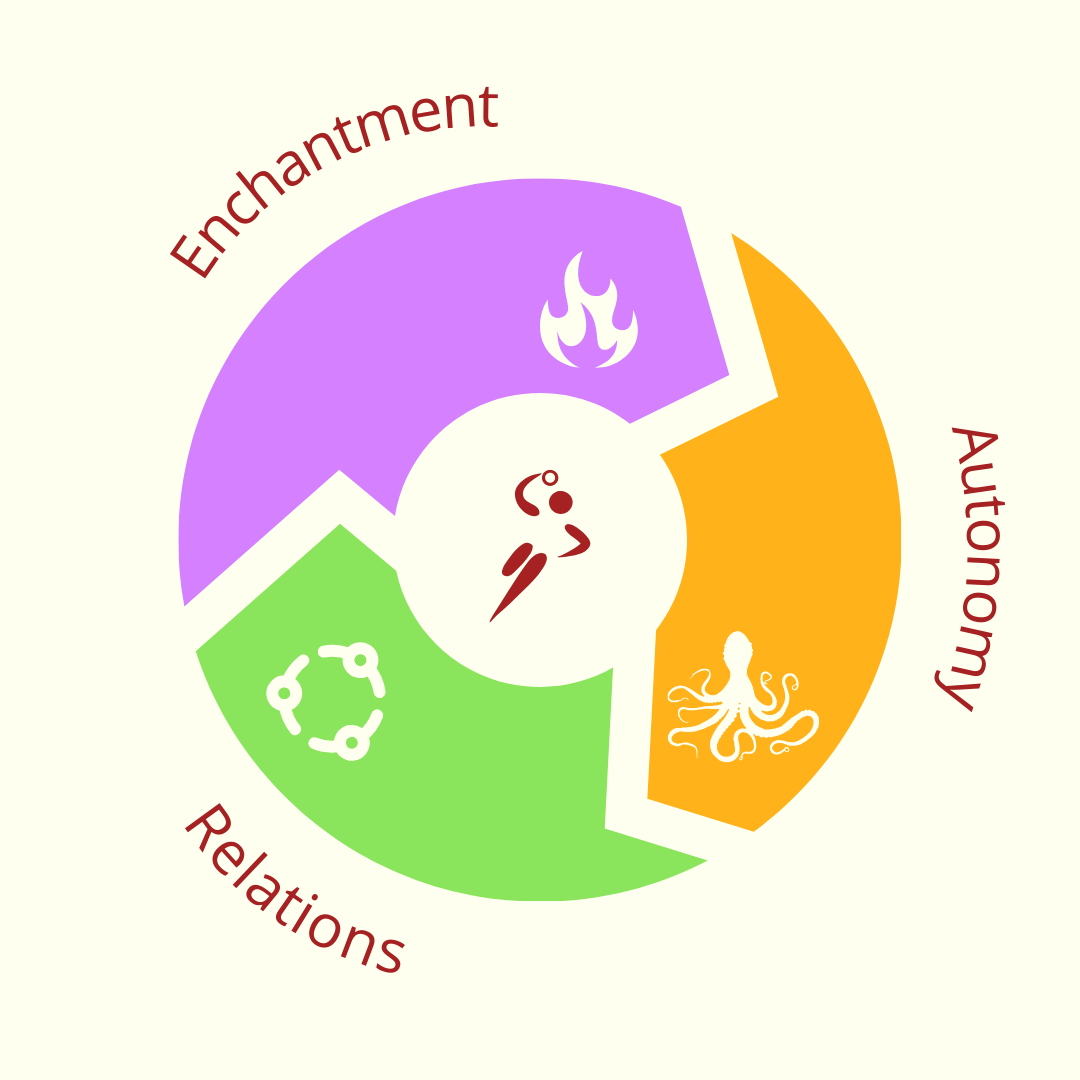

In this way, the science olympiads use the Olympic competition as a motor, as a playboard, to develop three sets of qualities:

- Enchantment or interest in the world: the perception that the world is much bigger and more diverse than we imagined, and the willingness to deepen its understanding and engagement with it;

- Autonomy: the capacity of self-activating, self-directing and self-regulating its own cognitive, metacognitive and emotional abilities, or the feeling of being able to deal with different situations using one's internal compass;

- Relations or shared culture: the joy and appreciation of sharing your knowledge and interests with peers; in other words, the Olympic environment is a place to make good friends.

In this way, whatever we learn comes in the form of something interesting, conducted with autonomy and shared in the community. That makes learning much more significant. And because it happens in several layers, that cultivation of values happens all the way from the local classroom and school level, the basis sustaining the other levels, to the international gathering, the tip that inspires the other levels.

But more specifically, how does the Linguistics Olympiads do it?

Linguistics Olympiads

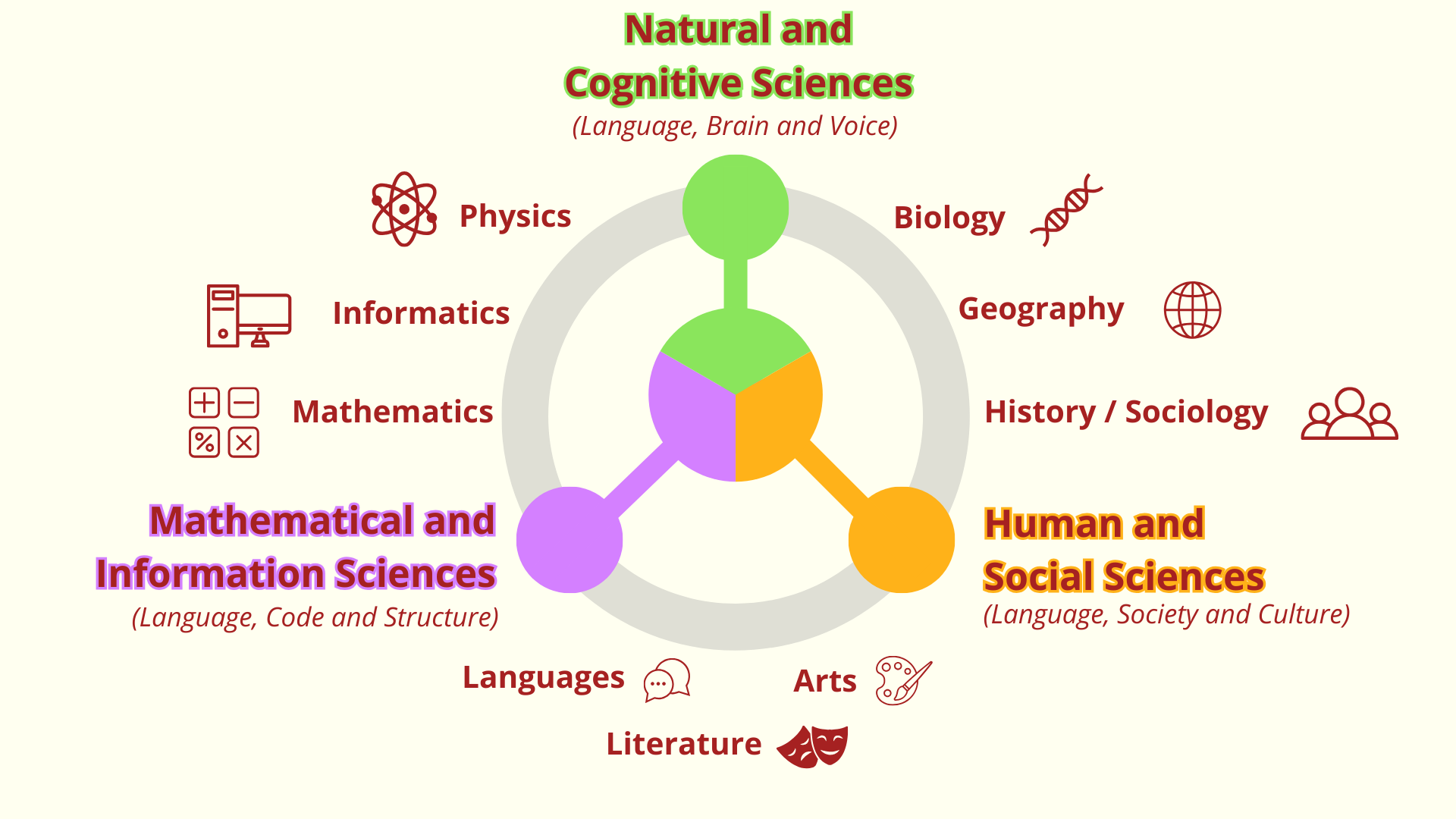

Among the science olympiads, a Linguistics Olympiad stands out by having a naturally transdisciplinary approach — after all, all disciplines are permeated by language. Thus, passing through the natural and cognitive sciences, the sciences of mathematics and information, and the human and social sciences, the linguistics problems act as integrators of knowledge, uniting analytic and cultural, mathematical and social, cognitive and communicational abilities.

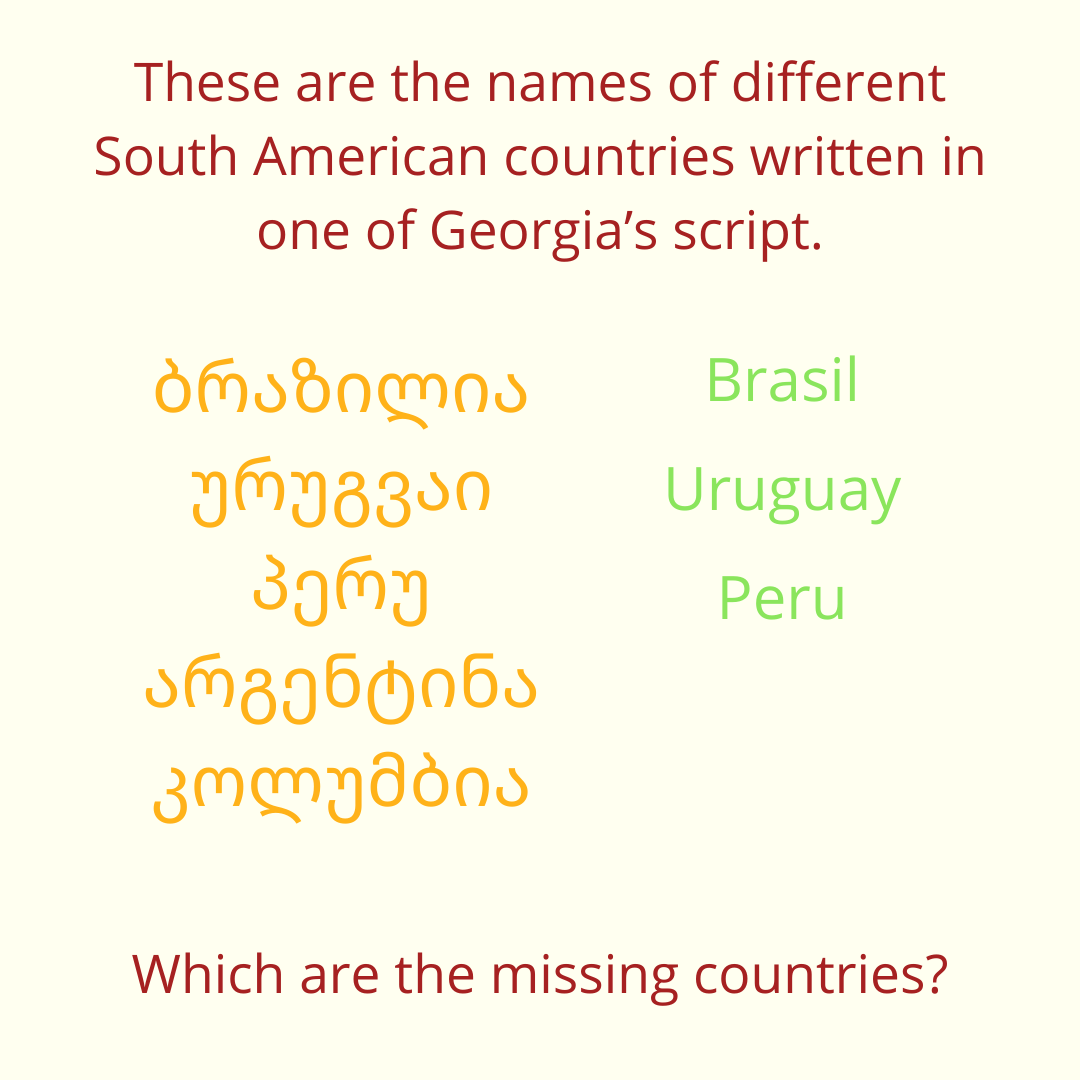

The Linguistics Olympiads mostly work with the genre of "self-sufficient linguistics problems", such as this example:

The idea is that, to solve the problem, the solver doesn't have to rely on proficiency in any other language or on theoretical knowledge about linguistics; instead, they have to use a good amount of reasoning, their linguistic intuition (as a speaker of at least one human language) and a piece of general knowledge about the world. By doing that, they end up discovering something that works differently in that language, interplaying between the diversity of cultural references and the unity of the human condition. In that way, reasoning, communicational skills and cultural sensibility work together to develop the capacity to deal with complex problems.

At school, linguistics problems can be a trigger device or focal point for working around different fronts: linguistic and cultural diversity; metalinguistic knowledge about one's own language; proficiency in additional languages; contact with scientific investigation about language; logic and reasoning; transversal dialogues across disciplines.

But what does it mean to the broader societal level?

Education, Language and Diversity

As an educational event, the Linguistics Olympiads aim at transforming individuals in the specific ways described before: by fostering interest in the world, autonomy with one's own capacities and good community relations, by using the interdisciplinary place of linguistics to work through multiple topics and developing reasoning, communicational skills and cultural sensibilities.

But a linguistics olympiad is also a political event, in the sense that it foresees and aims at certain transformations in the collective and structural levels of society. We aim to use the spotlights of the event to promote, discuss and perfect policies around three flags:

Linguistic and cultural diversity

Every language is a door to specific ways of seeing and relating with the world. Yet, despite the great diversity of human languages, most of the human population now speaks only a handful of languages, with at least 40% of the languages currently at risk of extinction. This concentration was further deepened with the waves of colonization and cultural imperialism in the last couple of centuries. In most cases, the threat against language diversity is also a threat against diversity in the ways of living — with many communities being stripped of access to the resources and conditions for sustaining their traditional ways of living and to the opportunity to decide for their own ways of incorporating elements from other cultures.

Several initiatives aim to give visibility and guarantee rights to these people, many of them reunited under the UN's International Decade of Indigenous Languages . In this way, Linguistics Olympiads aim to show and give a taste for the students about the linguistic diversity in their regions, contextualized with the particular linguistic situation of that region, raise awareness and snow what it means in terms of the diversity of cultures, knowledge and ways of living.

Languages as they are

A common misconception in the modern world is that there is one proper or correct way of speaking a language, and most speakers, dotted with an imperfect version of the language, should go to school to learn the proper way. Instead, the modern scientific study of languages abandoned long ago this assumption, showing that all manifestations of a language are equally functional, complex and practical, as they emerge from different patterning strategies in the mind of the speakers (as language is a natural faculty of the human mind) and of the usage of groups (as language exists to communicate and to convey different layers of meaning). Furthermore, modern studies of sociolinguistics started to show how this distinction of proper vs improper language fuels different dynamics of power within the society — in a way that linguistic prejudice is more often than not coupled with other forms of social prejudice since the most prestigious forms of the language are usually the forms of the social, geographic, ethnic or gender dominant groups.

In that sense, linguists in general, and the linguistics olympiad in general, aim to promote a more realistic way of dealing with languages, as real and natural manifestations of human conditions, and to raise awareness of the social and political dynamics involving languages. As such, we aim for school education to promote a more complex, nuanced and self-aware way of tackling the different linguistic registers and varieties, and for the State to promote language policies that mitigate the linguistic forms of social inequality and recognize the dignity of all speakers as true speakers of a true language.

Active and investigative education

Organized education is a commonly known keystone in the public policies of a country or region. Although we are increasingly aware of all the limitations in the traditional model of school education that has become the norm in the world, it is less obvious for the schools and the governments on how to make it better. Nevertheless, the last decades saw huge advances in cognitive, psychological and linguistic research that shows more precisely how education processes work in the human mind. Collectively, this research has been called sciences of learning. Furthermore, being a science olympiad, i.e., a problem-based, active and investigative learning process, we have very concrete knowledge of how to make learning more meaningful and effective.

As such, we aim to promote more active and investigative learning processes, impacting formal and informal learning in ways of making it more effective, interesting and transformative. For that we want not only to inform better educational public policies but also to bring concrete tools for teachers, school administrators and, of course, for the students themselves. After all, a worthy education process is one that makes the world an interesting place, oneself as a capable and self-aware person and the communities as nourishing and fulfilling spaces.